In the years after the French and Indian War, Britain's strategies to keep its Native American alliances sometimes backfired.

HUMANITIES, July/August 2015, Volume 36, Number 4

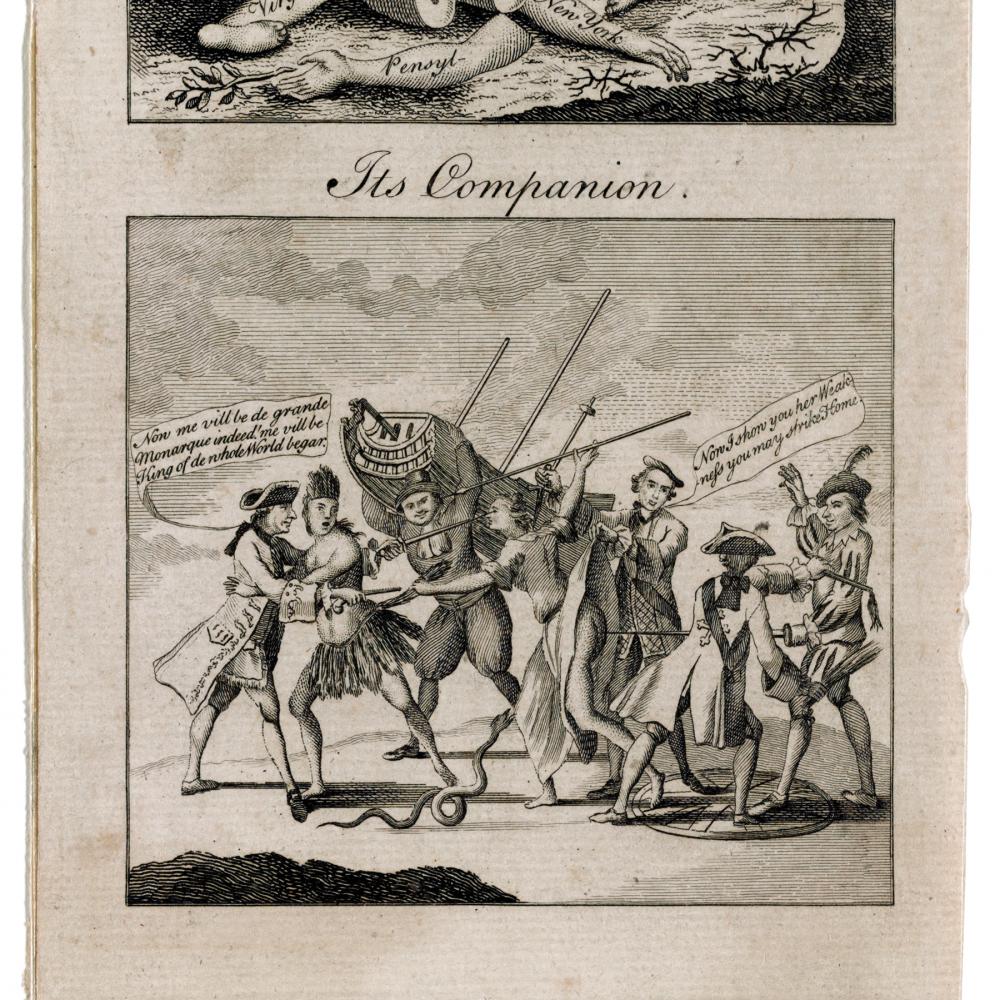

Above, Britannia dismembered and the colonies impoverished as a result of the Stamp Act. Below, Britannia is pictured as a woman and America as an Indian, both of them harassed,though America finds comfort in the arms of a Frenchman.

Library of Congress

John Trumbull’s painting Declaration of Independence is a classic depiction of history being made. From John Adams to Benjamin Franklin, all the key players appear to be in attendance. But are they?

John Trumbull’s depiction of Thomas Jefferson presenting a draft of the Declaration of Independence to Congress.

John Trumbull’s depiction of Thomas Jefferson presenting a draft of the Declaration of Independence to Congress.

In depicting only well-to-do white men, Trumbull ignored something like 95 percent of the people who participated in the American Revolution. Indians, slaves, small farmers, and women of all ranks played important roles when American colonists broke free of British control. In some cases, ordinary Americans very directly influenced the actions of the Founding Fathers. One little-known example involves a law Parliament passed two hundred fifty years ago. The Stamp Act, which took effect on November 1, 1765, was one of Britain’s most famous encroachments on colonial freemen’s rights. Its purpose, however, is little understood.

Contrary to popular myth, which has the British government adopting the Stamp Act to force Americans to pay down their share of its staggering debt, the real reason for the Stamp Act was to help fund a garrison of ten thousand British soldiers who remained in North America at the conclusion of an Anglo-French war in 1763. This was a sizable force: about the same number of troops Washington would have at Valley Forge fifteen years later.

Why weren’t these men sent home to Britain with their comrades? Thomas Gage, commander in chief of British forces in North America, explained in a December 1765 report to Lord Barrington, the secretary at war, that the redcoats had stayed behind because of “the Numerous Tribes of Savages who joined the French during the War, and over run our Frontiers.”

The Indian attacks of the 1750s and early 1760s shocked British officials as well as American colonists. Ever since Columbus’s time, natives had occasionally risen up against encroaching colonists—sometimes with rival colonizers as their allies. But for nearly a century, English and (after 1707) British monarchs had found, to their great relief, that whenever they went to war against their archrival, the king of France, they could count on significant native support in the American theater. That reassuring pattern, however, came to an abrupt halt during the conflict that is now widely viewed as history’s first global war.

It is known in Britain as the Seven Years’ War (since it officially began in 1756 and ended in 1763) and in Canada as the War of the Conquest (because during the war, in 1760, Britain captured Canada from France). Americans call it the French and Indian War because those two were the enemies, at least from a British perspective. For the first time ever, in fact, most of the Indian nations that participated in the interimperial conflict—including the Shawnee, Delaware, Miami Confederacy (on the Miami and Wabash rivers in present-day Ohio and Indiana), and the Anishinaabe in modern Michigan—took France’s side.

This left British officials determined to have at least some Indians at their side the next time they fought France. To be sure, Britain had captured Canada in 1760 without significant Indian support, but at great cost. Then as now, wars were by far the largest expense governments incurred, and the Seven Years’ War had almost doubled the British government’s debt. Imperial officials knew they would reduce their financial exposure in the next clash with France in proportion to the number of Indians who came in as their allies rather than their enemies.

But why had most Indians cast their lots with France? Imperial officials ended up attributing Indians’ animosity to two groups of Americans: fur traders and land thieves. For more than two hundred years, Europeans had traveled to America to sell manufactured goods to Native Americans in return for animal pelts. Many of these traders formed positive relationships with their customers and suppliers in the American interior. Some even married native women. On the other hand, relations between the Indians and the fur traders were often abusive. One common method of obtaining pelts at a favorable price was to trap natives in debt. In addition, General Gage accused British subjects who traded with the Indians of “making them drunk, and setting them one against another . . . which brought on Quarrells with the Provinces, and gave the Indians the Worst Opinion of all the English in General.”

Traders frequently used alcohol to lure Indians into signing fraudulent land deeds. In this they joined a crowded field, for territorial encroachment was another of the Indians’ principal grievances. Land fever pervaded colonial society. It infected individual settler families as well as large-scale speculators, such as George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and Benjamin Franklin, all of whom dreamed of acquiring title to thousands of western acres and then dividing them up into smaller parcels for profitable sale.

At the close of the Seven Years’ War, the British government adopted two major policies aimed at appeasing the Indians. On October 7, 1763, the king-in-council issued a proclamation drawing an imaginary line along the crest of the Appalachian Mountains. All of the land west of this so-called “Proclamation Line” would be reserved for the Indians.

Nearly a year before adopting the Proclamation of 1763, the government had decided to leave twenty-one battalions behind in North America after the war. Some of these ten thousand soldiers were posted to the regions Britain had just conquered from France, especially Quebec, with its eighty thousand French-speaking colonists. Others went to Florida, which before the Seven Years’ War had been Spanish territory.

The government positioned nearly half of its new American garrison in Indian country. The redcoats were there partly to maintain British forts for use in future wars against France and Spain. But they also had more immediate goals, and one was to protect the colonists from the Indians. As General Gage recalled in 1765, “The forts were maintained at the Peace for the purposes of keeping the Indians in awe and Subjection.” By investing up front in a barrier between the colonists and the Native Americans, the government hoped to avoid the much larger expense of a war against the Indians and whatever European allies they might attract. The thin red line of British soldiers between Indian and British American villages was like an insurance policy—and the idea, at least, was for the colonists to pay the premiums.